Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:16 — 18.2MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podchaser | Gaana | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | Anghami | RSS | More

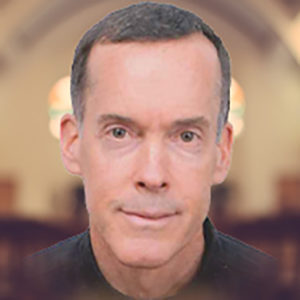

SJC17 – The Will in Prayer Inflamed by Pure Love – St. John of the Cross: Master of Contemplation with Fr. Donald Haggerty – Discerning Hearts Podcast

In this series Fr. Donald Haggerty and Kris McGregor discuss the depths of prayer as explored by St. John of the Cross, the Mystical Doctor of the Church.

An excerpt from St. John of the Cross: Master of Contemplation

It can be useful initially to recall the operation of inclination in the will, the first operation of the will, as described in chapter 5. The will by its natural inclination, in or out of prayer, seeks the satisfaction of taking possession of what it desires. This natural inclination plays a crucial role in prayer. The possibility in prayer is that on certain days the delight of consolation can be received in the course of prayer. This satisfaction, which may be graced, nonetheless can detour the soul from a pure pursuit of God if it becomes the primary desire sought in prayer. The desire for a spiritual taste or feeling, as Saint John of the Cross repeats often in his writings, may replace the far greater need to turn our desire fully and exclusively toward God himself in a great surrender to him. In a letter to a Carmelite nun in Córdoba written at almost this same time in July of that same year, he writes: “To possess God in all, you should possess nothing in all. For how can the heart that belongs to one belong completely to the other?” (L17). The pure desire for God himself has to be a consuming need for a soul that would love God with intensity. Secondary desires for experiences of satisfaction in prayer must be understood as an inferior pursuit.

This teaching entails further insights and challenges. Nothing that can be enjoyed as a satisfaction in prayer should be interpreted as taking hold of God, just as no knowledge of God received in prayer is equivalent to comprehending the actual truth of God. No taste of the presence of God in prayer removes the inaccessibility of God in his divine nature to the human soul’s immediate experience. To think otherwise is to be deceived. It is necessary, then, not to halt at any experience of satisfaction in prayer as though a possession of God had been enjoyed in this delight. On the contrary, the soul must accept that the deeper truth of prayer extends always beyond any experience in prayer. The inclination of the will in prayer should remain ever desirous for God himself without arriving, as it were, at a destination in some satisfaction. In truth, a pure desire for God never arrives at a final satiation in this life, but rather is inflamed increasingly over time with an intensifying desire for God. If we enjoy some delight in prayer on any day, this experience does not convey the deeper truth of prayer, which is often concealed within unseen layers of the soul.

Haggerty, Donald. Saint John of the Cross: Master of Contemplation (pp. 270-271). Ignatius Press. Kindle Edition.

For more episodes in this series visit Fr. Haggerty’s Discerning Hearts page here

You find the book on which this series is based here