VATICAN CITY, 14 SEP 2011 (VIS) –

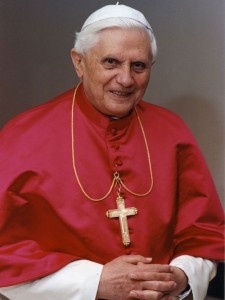

This morning the Holy Father travelled by helicopter from the Apostolic Palace at Castelgandolfo to the Vatican, where he held his weekly general audience in the Paul VI Hall. In his catechesis he dwelt on the first part of Psalm 22, focusing on the theme of prayers of supplication to God.

The Psalm, which remerges in the narrative of Christ’s Passion, presents the figure of an innocent man persecuted and surrounded by adversaries who seek his death. He raises his voice to God “in a doleful lament which, in the certainty of faith, mysteriously gives way to praise”.

The Psalmist’s opening cry of “my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” is “an appeal addressed to a God Who appears distant, Who does not respond”, said the Holy Father. “God is silent, a silence that rends the Psalmists heart as he continues to cry out incessantly but finds no response”. Nonetheless, he “calls the Lord ‘my’ God, in an extreme act of trust and faith. Despite appearances, the Psalmist cannot believe that his bond with the Lord has been severed entirely”.

The opening lament of Psalm 22 recurs in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark in the cry the dying Jesus makes from the cross. This, Benedict XVI explained, expresses all the desolation the Son of God felt “under the crushing burden of a

mission which had to pass through humiliation and destruction. For this reason He cried out to the Father. … Yet His was not a desperate cry, as the Psalmist’s was”.

Violence dehumanises

Sacred history, the Pope continued, “has been a history of cries for help from the people, and of salvific responses from God”. The Psalmist refers to the faith of his ancestors “who trusted … and were never put to shame”, and he describes his own extreme difficulties in order “to induce the Lord to take pity and intervene, as He always had in the past”.

The Psalmist’s enemies surround him, “they seem invincible, like dangerous ravening beasts. … The images used in the Psalm also serve to underline the fact that when man himself becomes brutal and attacks his fellow man, … he seems to lose all human semblance. Violence always contains some bestial quality, and only the salvific intervention of God can restore man to his humanity”.

At this point, death begins to take hold of the Psalmist. He describes the moment with dramatic images “which we come across again in the narrative of Christ’s Passion: the bodily torment, the unbearable thirst which finds an echo in Jesus’ cry of ‘I am thirsty’, and finally the definitive action of his tormenters who, like the soldiers under the cross, divide among themselves the clothes of the victim, whom they consider to be already dead”.

At this point a new cry emerges, “which rends the heavens because it proclaims a faith, a certainty, that is beyond all doubt. … The Psalm turns into thanksgiving. … The Lord has saved the petitioner and shown him His face of mercy. Death and life came together in an inseparable mystery and life triumphed. … This is the victory of faith, which can transform death into the gift of life, the abyss of suffering into a source of hope”. Thus the Psalm leads us to relive Christ’s Passion and to share the joy of His resurrection.

In closing, the Pope invited the faithful to distinguish deeper reality from outward appearance, even when God is apparently silent. “By placing all our trust and hope in God the Father, we can pray to Him with faith at all moments of anguish, and our cry for help will turn into a hymn of praise”.

AG/ VIS 20110914 (630)

Published by VISarchive 02 – Wednesday, September 14, 2011

hy, O

hy, O  THE INTERIOR CASTLE

THE INTERIOR CASTLE