I leave it to Omar F. A. Gutierrez to write so well on the life,  times, and death of this great saint.

times, and death of this great saint.

You may perhaps remember a scene from Braveheart with Robert the Bruce and his father the leper.

When his son first brings him news about the rebellion led by William Wallace, a commoner, the father instantly devises a plan by which the Bruce clan can gain favor with the Scots and with the English. You get the feeling that Robert is a bit taken aback by the so easy and cold calculation of his rotted father.

He says,

This Wallace. He doesn’t even have a knighthood. But he fights with passion, and he is clever. He inspires men.

His father replies:

You admire him. Uncompromising men are easy to admire. He has courage. So does a dog. But you must understand this: Edward Longshanks is the most ruthless king ever to sit on the throne of England, and none of us, and nothing of Scotland, will survive unless we are as ruthless, more ruthless, than he.

“Uncompromising men are easy to admire.” There is in this world, and it seems more so today, a habit of admiring the compromising fellow. With the ubiquitous dictatorship of relativism that oppresses so many minds, it only makes sense that the general public would take offense at anyone who dares stand up for something with uncompromising stolidity.

The holder of objective truth claims is – so the sages of Manhattan and Melrose Place tell us – no different than the Nazi who insists on the claim to racial purity or the Islamic bomber who literally does cling to his religion and guns.

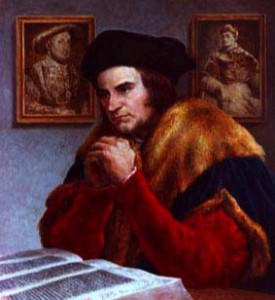

For this reason, the figure of St. Thomas More, whose feast it is today, can be such a  perplexing figure for the modern mind. And even the Catholic who consumes their breakfast whilst pouring over the latest moto proprio can miss this astonishingly great man. I have to admit having skipped over him in my studies, chalking him up with all the other saints and blesseds who gain God’s favor by losing their heads. But St. Thomas More is more than just a martyr.

perplexing figure for the modern mind. And even the Catholic who consumes their breakfast whilst pouring over the latest moto proprio can miss this astonishingly great man. I have to admit having skipped over him in my studies, chalking him up with all the other saints and blesseds who gain God’s favor by losing their heads. But St. Thomas More is more than just a martyr.

He’s an example of such exquisite lack of compromise that he can teach us a great deal about the Catholic Social Doctrine we long to understand and live out.

The Educated Man

Thomas was born in February 1478 to Sir John More and Agnes Grainger just blocks from St. Paul’s Cathedral (Milk Street, Cheapside). He was well born into a wealthy family that could afford to send him to St. Antony’s and then eventually, by the time he was twelve, to Oxford.

Right from the start of his life, one finds an interesting bit. Sir John was very strict with his son. There were no bacchanalian romps like those we read about in Waugh while the young More was at Oxford Christchurch. Thomas’ father saw to that by giving him only enough money for necessities. I am reminded, then, of this line by Blessed John Paul II in Familiaris consortio

37. Even amid the difficulties of the work of education, difficulties which are often greater today, parents must trustingly and courageously train their children in the essential values of human life.

And on what are those essential values founded?

Children must grow up with a correct attitude of freedom with regard to material goods, by adopting a simple and austere life style and being fully convinced that ‘man is more precious for what he is than for what he has.’(Guadium et spes 35)

Freedom not from the state or from stodgy schoolmasters or from bourgeois, patriarchal, social structures, no. What children need is freedom from an overly active attachment to stuff.

Thomas More, because of his lack of time to do much else but to study his dear Latin, ends up going to law school in 1496. By 1501 he passed the bar and in 1504 he became a member of Parliament.

The Spiritual Man

During this time of study, young Thomas fully adopted the hard-won lessons taught by his father. When he was eighteen, he began wearing a hairshirt, a practice he continued until his dying day. He went to daily Mass, a rarity in those days. He prayed all the regular penitential prayers for Fridays, and prayed the Little Office.

Unlike some saints, however, St. Thomas More did not “overdo it.” There are countless examples of saints who have to be told by superiors to “lighten up” on their penances. Some saints learn the hard way that they cannot be so stern towards their bodies. Indeed, St. Francis is reported to have said before he died that his one regret was having treated his body, Brother Ass, so harshly. No, More was ascetical, but not loony. Erasmus, his dear friend, once wrote of him:

I never saw anyone so indifferent about food…. Otherwise, he has no aversion from what gives harmless pleasure to the body.

As before, Thomas understood that the best education was one which taught you how to have a proper detachment from things. In this was virtue, and Thomas pursued virtue with vigor.

Desiderius Erasmus is an interesting figure of history who is controvertible in many circles but perhaps for only the wrong reasons. Erasmus and More were close because the two of them loved the Greek and Latin languages and they would “play” at translating Greek epigrams into the language of the Church. Their mutual friend William Lily was actually the first man to teach the Greek language in London. This was the sort of pleasure that young Thomas More sought out.

Now, you can imagine that he seriously considered the priesthood. I find this aspect of Thomas’ life interesting as there are so many of our male youth – myself included at one time – with this sort of floppiness regarding vocation. Thomas was drawn to the Carthusians, the Franciscans and to the diocesan priesthood. He could not, it seems, decide which way God was calling him. Perhaps he waffled back and forth because he felt he ought to be a priest though he did not feel the call. Whatever the case, More did not attempt the life of the cleric. Rather, he chose marriage.

The Family Man

Enter Jane Colt. Jane was the eldest daughter of John Colt of Netherhall, Essex. This is significant because the Colts were not nobles or wealthy Londoners. They were the pure and simple folk of the English countryside, the same people that Tolkein and Chesterton and Belloc and Lewis and all of us know to be the steadfast and good folk that inspires characters like the semper fidelis Sam Gamgee.

Thomas married Jane after, it seems, having first been infatuated with Jane’s younger sister. William Roper, More’s future son-in-law, tells us that after realizing what an offense it would be for him to pursue the younger sister while the older was unmarried, he “took pity” on Jane and chose her. Roper’s version of this is perhaps a bit harsh. By all other accounts, Thomas exemplified yet again his uncompromising desire to do good and avoid evil by taming his desires and bending his will towards the right.

“Pity” is not the right word to describe More’s attitude towards Jane. Thomas again shows us that he is not attached to things, to outward appearances, or to conquests of a bewitching woman. Rather than court the younger sister, he pursued Jane, came to know her, fell in love with her purity and virtue and married her in 1505, showing that infatuation is for the fat headed.

He and Jane had four children: Margaret (Meg), Elizabeth, Cecilia and John. Now poor Thomas loses his dear wife in 1511. So at the time of their mother’s death, these children ranged in age from around six to about two. Within months of his wife’s passing More marries Alice Middleton, a woman seven years his senior, a widow and mother to several children only the youngest of which joined the More household.

Here, the marriage of More and Middleton becomes a bit comical. Unlike Jane, Dame Alice was not so willing to put up with Thomas’ long visits with his learned friends, who would mill about sipping on wine and discussing the intricacies of Greek and Latin grammar. Alice was a practical woman, which is most likely why More married her. He teased her on occasion, and she would complain about his hairshirt. He would try to tell her about the latest scientific theory, and she would berate him for not being ambitious enough. They both would give as good as they got.

Once, in response to the question about why both Jane and Alice were petite women, More said:

If women were necessary evils, was it not wise to choose the smallest evil possible?

On another occasion when writing to a Dutch friend, Dame Alice made her husband write:

My wife bids me give you a thousand greetings, and thank you for your very careful salutation, in which you wished her a long life, of which she says she is all the more desirous, that she may plague me the longer.

Humor was a good part of the More household as was religious piety. Every evening, the entire household gathered for prayers, that is servants, cooks, stable men and boys, friends, visitors, all gathered. During dinner a passage and commentary on Scripture would be read by one of the children while everyone else listened. After that was done, then talk about their days would ensue.

Nobles were rarely if ever invited to dinner, and the wealthy only occasionally. More’s brighter friends, those lovers of Greek and Latin like Erasmus, would visit and spend long nights. But More was also in the habit of going out into the village to invite the poor to come and sup.

Good Thomas More was also known for insisting that he be told whenever a woman from the village was going into labor. When informed he would pray for her throughout the night if necessary until he was told about the outcome. Good or ill, he would often take the time to travel to the home of the newborn to greet the family and offer his help.

Friends, this is not the stuff of a weak-kneed sap-of-a-saint, who with rosy cheeks appears on our saint cards awash in light and glitter. This was a man who lived life to serve, and to do so in the Spirit of the Savior. In short, St. Thomas More was a righteous man before he ever ran up against the intemperate nature of Harry, king of England.

The Vicious Man, Henry

King Henry VIII had been crowned the King of England in 1509 at the ripe old age of eighteen. Remember that at the same age More was wearing hairshirts and attending daily Mass. King Harry was instead debauching young lasses as best he could.

In the age of arranged marriages for kings and queens, it was proposed by Spain – the seat of the Holy Roman Empire at the time – and by England and Rome that Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of the famed Ferdinand and Isabella, might marry Harry’s brother Albert. Well, Al was sickly, and though the marriage took place it was certainly never consummated. Indeed, Henry VIII counted on this fact when he decided to marry Catherine himself, about whom he had grown quite obsessed. They had several pregnancies but only one surviving child, Mary.

What follows is the sad history of the betrayals of King Henry against poor Catherine. Protestant or Catholic, nearly everyone recognizes that Catherine of Aragon was treated most dreadfully by Henry. After siring an illegitimate son with one woman, he took up with Mary Boleyn who was married to another man. Henry, though, grew tired of her and pursued her sister Anne Boleyn.

It was Ann who pressed Henry to get rid of Catherine. It was the Boleyn family chaplain Thomas Cranmer who was made the Archbishop of Canterbury and who nullified the marriage between Catherine and the King. It was the Boleyn family friend Thomas Cromwell who persecuted St. Thomas More and proceeded with Cranmer and King Harry to sack every Catholic monastery in England once their own church was founded. Indeed, it could very well be said that it was the Boleyn family that brought down the Catholic Church in England, and all of it because of the tempestuous and inconstant nature of King Henry VIII.

The Uncompromising Man

In contrast, then, we have Thomas More, who had become Lord High Chancellor of England in 1529 after Cardinal Wolsey failed to secure the annulment of marriage for Henry. Thomas More knew he could not last long as the Chancellor if he did not support the annulment with Catherine, and he didn’t. He resigned his post in 1532.

Right away, then, we see that he would rather put his family’s fortune a risk than to violate his conscience against the truth. I can hear in my own mind that little voice the pops up to say, “It’s only a little lie,” or “who will know or care?” or “don’t quit, stay part of the system so that you can change it for the good.” No, More understood that the power he wielded as Chancellor would corrupt as surely as Sauron’s ring of Power, even with his good intentions, should he violate his conscience.

For the next year and half the More family learns to live rather frugally. More engages in writing some tracts against this or that heresy, and about matters of law, but does not comment on the situation with that Boleyn girl and the King. He refuses to attend the coronation of Anne.

In 1533, when Cranmer marries Boleyn and the King, the Holy Father excommunicates them all. In 1534 the King introduces to Parliament the Act of Succession law which requires all to recognize Anne as the rightful queen and her offspring, namely Elizabeth, as the rightful heir. To refuse to accept this decree is to admit to treason.

Thomas More, widely respected figure that he is, is asked to comment on the Act. He gives none. He is asked again and pressed, but he gives none. Eventually he is put under house arrest, then carted off to some holding area, and then sent to the Tower of London where he spends the next fifteen months.

Here, we find More alone in a cell. He hasn’t denied or admitted to anything. He simply refuses to give in opinion on the matter. But King Henry knows this is not good enough. He needs More on his side. Cromwell knows the same.

Dame Alice, Margaret and her husband William Roper, and other friends attempt to persuade Thomas against his silence. Compromise. You can almost hear the leper father of William the Bruce saying it:

Uncompromising men are easy to admire. He has courage. So does a dog.

Our world, the world of the politically savvy, would tell us that it takes a strong man to compromise, to recognize when he’s beat and to move on for the greater good. But More would not compromise. For the sake of truth he could not compromise any more than he could deny the existence of his own right hand.

While in prison, More wrote this:

Give me, good Lord, a longing to be with thee : not for the avoiding of the calamities of this wicked world, nor so much for the avoiding of the pains of Purgatory, nor of the pains of Hell neither, nor so much for the attaining of the joys of Heaven in respect of mine own commodity, as even for a very love of thee.

More understood that the greater good was to be with the good Lord. Note that. Despite the turn of fortune in life and the lives of many of his loved ones, he still prays with “good Lord.”

Friends, we know what happens to More. On July 6, 1535 he is taken to the scaffold. He walks up the steps and exchanges a joke with the guard. He greats the executioner and wishes him well. He announces that he is dying for the Catholic Faith and declares himself:

The King’s good servant – but God’s first.

This family man, this political figure, this lawyer, this saint shows us that losing one’s head is not what makes us close to God. Rather it is the attitude towards this world that is simultaneously detached from the what’s, while being attached in service to the who’s.

Anne Boleyn – with no male heir, she couldn’t be annulled, so Henry accused her of treason and she was beheaded in 1536.

St. Thomas More is almost the perfect example of what Catholic Social Teaching is. He understood that the political life was not the end for the human person. People are the ends of political life, and the fulfillment of their potential. A conscience in tune with the will of God and a society that allows for that pursuit of the divine, the adventure of orthodoxy that Chesterton describes, that is living. But this is only possible if we accept truth. About this we must be uncompromising.

Sure we may come off as brutish and closed. But then, St. Thomas More shows us that to be uncompromising for the truth is to live in the righteousness of the God who loves.

And finally, More shows us that that love in truth is founded first in the family. From his own father to the way he fathered his children, More showed himself as a prime example of what Blessed John Paul II goes on to say after the quote from above:

In a society shaken and split by tensions and conflicts caused by the violent clash of various kinds of individualism and selfishness, children must be enriched not only with a sense of true justice, which alone leads to respect for the personal dignity of each individual, but also and more powerfully by a sense of true love, understood as sincere solicitude and disinterested service with regard to others, especially the poorest and those in most need. The family is the first and fundamental school of social living: as a community of love, it finds in self-giving the law that guides it and makes it grow.

St. Thomas More was a man who practiced in the law of self-giving. That law of love in the family is founded on marriage, and More knew this. About our care for the defense of the sanctity of marriage we cannot back down. We cannot be compromising. Though we may not have the articulation for it, we ought to stand firm. Though we are and will continue to be persecuted for it, we must live and serve “true love.”

St. Thomas More, pray for us. And long live Christ the true King.